The News & Observer recently reported that Durham county commissioners voted unanimously to work with the school district on a financial plan to increase hourly wages for bus drivers, cafeteria staff, janitors and substitute teachers employed in Durham Public Schools to $15 an hour.[1] That is great news and certainly action by the county commissioners to be commended!

Aside from moving in the direction of a livable wage, Michelle Burton, president of the Durham Association of Educators, was quoted in the article saying, “the board’s decision is significant from a racial equity perspective. If you look at the composition of the folks who work in those positions, they’re primarily women of color, Black and brown women. A lot of our custodians are African American and Latino. Our child nutrition, African American women.”[2]

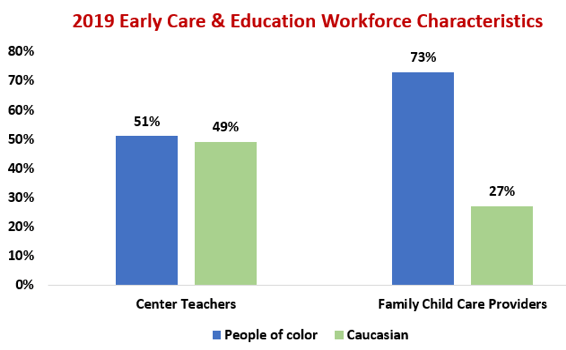

It is important and celebratory to see a commitment to increase wages for public school employees; there is another workforce that is also comprised of a majority of people of color (overwhelmingly women) who also support our state’s education infrastructure who continue to labor at low wages despite their importance to promoting the healthy development of children.

Last month, Child Care Services Association (CCSA) released its latest report[3] sharing the results of a 2019 early care and education workforce survey. Despite the important work that child care teachers do related to the early learning of children, at a time when science shows their brains are developing the fastest setting a foundation for all future learning (including school readiness and school success), early educators continue to earn low wages.

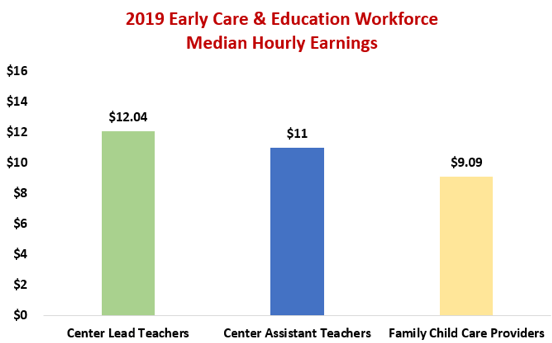

For example, CCSA’s latest report shows child care teachers earn on average about $12 per hour.

Teacher assistants earn about $11 per hour. Family child care providers earn about $9.09 per hour.[4]

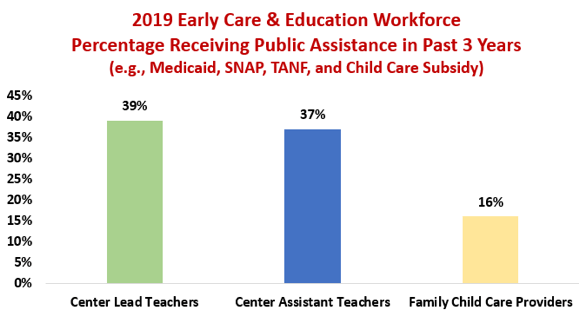

As a result, turnover is high, about 13% of child care teachers and 16% of assistant teachers work two jobs, and more than one-third of the child care teaching workforce relies on public benefits.[5]

For example, the most recent survey found that 39% of child care teachers, 37% of assistant teachers and 16% of family child care providers had received some type of public assistance (e.g., Medicaid, SNAP, TANF or child care subsidy) in the past three years.[6]

In April, the NC Division of Child Development and Early Education (DCDEE) recognized the importance of the child care workforce and paid bonuses of $950 per month for full-time teaching staff and $525 per month for non-teaching staff.[7] At $950 per month for those working onsite in child care, this was a raise of $5.48 per hour for those working full time and $4.88 per hour for those working part-time (an average of 25 hours per week). Bonus payments, however, ended in June.

The public health pandemic continues to impact communities throughout North Carolina and child care workers are on the front line. As an industry supporting the public, the likelihood of their exposure to COVID-19 is greater than for other workers. While child care programs are adhering to public health guidance and additional health and safety precautions in their daily operations, workforce pay continues to not reflect the important jobs that they do.

Our nation has learned what the early childhood field has always known, that child care is truly essential to the larger workforce and to the economy. Early educators are the workforce behind the workforce because parents cannot go to work without care and education for their children, and specifically, care that they trust. Yet, teachers are leaving their centers for better paying jobs and some are unwilling to return; thus we have a perfect storm of chronically low pay and health risks they must face each time they step into their child care programs. These jobs are truly in demand at this time because the field cannot find enough teachers to meet the need and the poverty-level wages are the primary barrier.

In the short-term, should Congress appropriate additional funding for child care later this month, bonus pay should be awarded to child care heroes who are working to support economic recovery as well as the early learning of children. In the long-term, it’s time to rethink child care compensation so that the early learning workforce is paid in a manner aligned with their credentials and experience.

Like with the decision by the Durham County Board of Commissioners to increase hourly wages for school system bus drivers, cafeteria staff, janitors and substitute teachers, it’s time for state legislators and state agencies to increase hourly wages for the workforce of our youngest learners. The current wage structure for the child care workforce is based on what parents can afford (i.e., the operating budget of child care programs is largely comprised of fees from parents). Parents can’t pay more and, therefore, without a public funding strategy, wages are at a standstill.

The workforce that supports all other workforces deserves better. It’s time to set up a series of video meetings to discuss options to fund the salary scale developed and studied. Where there’s a will, there’s a way. Let’s commit in the new year to harness that will.

[1] The News & Observer, Durham County to raise pay of school cafeteria staff, bus drivers to $15/hour, November 24, 2020.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Child Care Services Association, 2019 North Carolina Child Care Workforce Study, November 2020.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] NC Division of Child Development and Early Education (DCDEE), COVID-19 Child Care Payment Policies, April 2020.

[8] Source for Charts: Working in Early Education in North Carolina, Child Care Services Association, 2020.