Since March 14 when all public schools across North Carolina were closed for in-person instruction, along with most Head Start programs, families with young children throughout the state have struggled to keep their families safe from COVID-19 exposure and illness, balance jobs and caregiving responsibilities, as well as support remote learning to the extent offered and possible.

These challenges were made more difficult as the pandemic months wore on, which were hard for the wealthiest of families let alone those families who struggled to find and afford child care, who lost jobs or had a reduction in income or lacked access to the internet or technology such as a laptop or tablet to help support their children’s “remote learning.” It’s no wonder there has been a significant increase in anxiety, stress and depression.[1]

This week, the NC Division of Child Development and Early Education (DCDEE) released new guidance for NC Pre-K programs operating this fall.[2] DCDEE strongly encourages NC Pre-K programs to prioritize having students physically present in Pre-K classrooms for the 2020-2021 school year.[3] Why? Because children learn best in-person – not through screen-time. Programs will operate for a full 36 weeks as usual, 6.5 hours per day, 5 days per week, beginning no later than September 8.

The goals are clear[4]:

- All NC Pre-K students receive the benefit of fully in-person instruction to the fullest extent possible.

- All parents/guardians are offered the option of in-person instruction for the full program year.

- Remote learning will be available for NC Pre-K students as a last resort and used as sparingly as possible.

Because many NC Pre-K classrooms are operated in community-based child care centers, it is possible to operate NC Pre-K classrooms even while public schools are closed or switch to a hybrid model where Group A may attend two days per week and Group B may attend another two days in that week. Because child care centers are typically much smaller settings compared to public elementary schools and because pre-K classrooms generally have fewer students per class than the average K-6 classroom in public schools, pre-K operating within child care centers makes sense as an option for those parents who select it. Unlike public school attendance, participation in NC Pre-K is voluntarily selected by parents.

What we know is that COVID-19 took us all by surprise this spring.

Public schools and NC Pre-K shifted to remote learning in a heroic effort to promote continued learning while facilities were closed. At the same time, despite those heroic efforts, remote learning was at best an experiment. Little is known about its effectiveness. And, effectiveness compared to what – compared to onsite instruction? Compared to the absence of any learning packets, phone calls, texts or online engagement? What we do know is that remote learning is not the best format for 4 year-olds. There is no 4 year-old who can engage in remote learning without the support of an onsite parent or guardian. And, whether or not 4 year-olds are home with an older sibling while parents work, or have parents or grandparents who are not otherwise working or caring for other children so that they can devote the specific, individual time needed to support their 4 year-old’s remote learning is a real question. Unanswered to date.

In July, Duke University’s Center for Child & Family Policy released the results of a statewide survey of NC Pre-K lead and assistant teachers.[5] On average, lead and assistant teachers reported that the highest percentage of children in their classrooms received remote learning services weekly – 58 percent of children reported by lead teachers and 62 percent of children reported by assistant teachers.[6]

Unlike the daily onsite NC Pre-K program of 6.5 hours, only one-third of children reported by lead teachers received daily remote learning services (27 percent of children reported by assistant teachers received daily remote learning services).[7]

When asked about remote learning strategies most often used, in declining order by most often used were: phone calls and texting at #1, learning or activity packets at #2, email at #3 and Zoom and ClassDojo at #4 (video connections).[8] Certainly, teachers are to be commended for their outreach efforts, but at the same time, these efforts are really not comparable to the 6.5-hour regular onsite program.

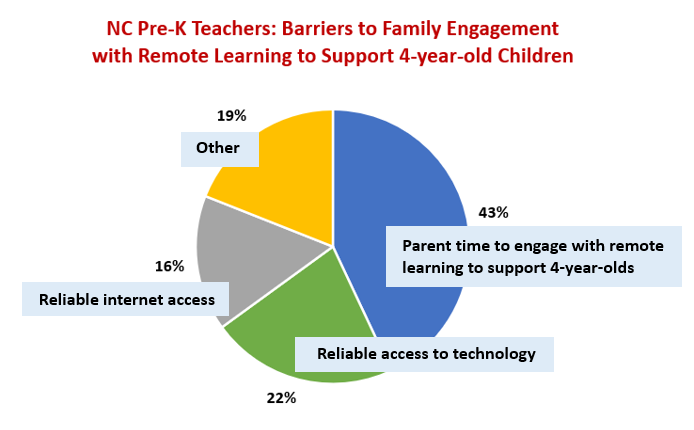

Duke’s study also reported teachers’ perceptions on the greatest barriers to family engagement with remote learning. Time to engage with remote learning was rated as the largest barrier to family engagement (43 percent reported by lead teachers, 45 percent reported by assistant teachers), followed by reliable access to technology (22 percent reported by lead teachers, 23 percent reported by assistant teachers), reliable internet access (16 percent reported by lead teachers, 21 percent reported by assistant teachers) and some other barrier (19 percent reported by lead teachers, 11 percent reported by assistant teachers).[9]

Were there lessons learned from the remote learning experience from this past spring?

Yes. And, many are reflected in extra training and supports for NC Pre-K staff in the coming year. Yet, the biggest takeaway is that remote learning is still an experiment. And, that’s why it makes sense that the new DCDEE guidance emphasizes a priority for in-person NC Pre-K classrooms to the extent possible.

The most recent data shows 2,689 child care centers open throughout North Carolina.[10] On average, child care centers show enrollment of about 53 percent.[11] This means that many could have additional space to support pre-K classrooms should they be inclined to partner within their community to offer NC Pre-K. Statewide, more than 100,000 children are in licensed child care.[12] These children are in programs following public health safety and social distancing guidelines.

Existing research pertaining to online learning for K-12 students raises serious questions about remote learning effectiveness.[13],[14] A National Institute for Early Education Research (NIEER) study related to public pre-K students this spring found that only 23 percent of children previously served in public pre-K programs (pre-COVID-19) continued to receive meals and nutritious snacks.[15] Nearly one-quarter of public pre-K students with disabilities received no support and about 40 percent of pre-K students with disabilities received only partial support.[16]

Given what we know about the school readiness gaps by income, by race, by ethnicity and the limited but questionable effectiveness of remote learning for 4 year-old children, DCDEE’s guidance recommending prioritizing in-person NC Pre-K instruction makes sense. With child care centers open and adhering to public health guidance on social distancing and experience serving the children of essential personnel this spring, it makes sense to give parents the option of enrolling children for onsite instruction this fall. There will be families who decide the onsite option is not for them. There could very well also be families who see the availability of onsite instruction as an opportunity for their children.

Utilizing child care centers as community partners makes sense. They are open for child care. It seems inconsistent to say that they can offer child care but not NC Pre-K. Local communities will be deciding soon. Decisions about onsite pre-K classrooms should not be linked to the operating status of public schools but whether capacity exists within community-based child care programs to safely follow Department of Public Health guidance to offer both child care and public pre-K. Children and working families depend on it.

[1] U.S. Census Bureau Household Pulse Survey, Week 12, July 16-July 21, 2020.

[2] NC Division of Child Development and Early Education (DCDEE), Interim COVID-19 Reopening Policies for NC Pre-K Programs, August 3, 2020.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Duke University, Center for Child & Family Policy, The North Carolina Pre-Kindergarten Program and Remote Learning Services During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Findings from a Statewide Survey of Teachers, July 2020.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Child Care Resources Inc. (CCRI), July 2020.

[11] DCDEE, July 2020.

[12] DCDEE, July 2020.

[13] Molnar, A., Miron, G., Elgeberi, N., Barbour, M.K., Huerta, L., Shafer, S.R., Rice, J.K. (2019). Virtual Schools in the U.S. 2019. Boulder, CO: National Education Policy Center.

[14] OECD (2015), Students, Computers and Learning: Making the Connection, PISA, OECD Publishing.

[15] National Institute for Early Education Research (NIEER), Young Children’s Home Learning and Preschool Participation Experiences During the Pandemic, NIEER 2020 Preschool Learning Activities Survey: Technical Report and Selected Findings, July 2020.

[16] Ibid.