Last month, Child Care Services Association released an issue brief, Addressing the Early Childhood Workforce Crisis through Stabilization Grants, which summarized the important role that NC Early Childhood Stabilization Grants have played in supporting child care programs statewide. Five case studies demonstrated the ways in which these funds have been invested such as supporting operating costs and increasing staff pay and benefits.

As welcome and helpful as the NC Early Childhood Stabilization Grants have been, the ongoing pandemic continues to impact the child care industry.

Working parents in North Carolina

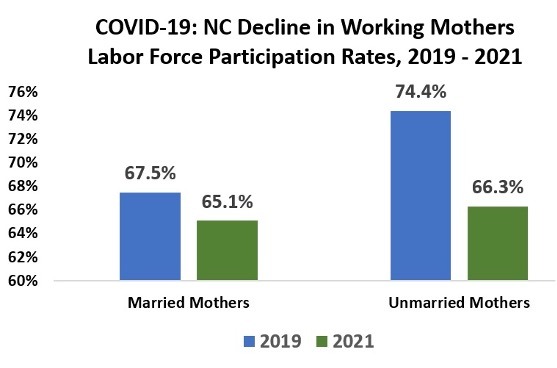

NC Married Mothers. In 2019, 67.3% of married mothers with children age 14 and younger were in the labor force. In 2021, only 65.1% of married mothers with children age 14 and younger were working, an increase from the sharp drop in working mothers that occurred in 2020, but still a decline of 2.2 percentage points.[1]

NC Single Mothers. In 2019, 74.4% of unmarried mothers with children age 14 and younger were in the labor force. In 2021, only 66.3% of unmarried mothers with children age 14 and younger were working, an increase from the decline in 2020, but still 8.1 percentage points below 2019 before the pandemic took hold across the country.[2]

The most recent U.S. Census Bureau Household Pulse Survey found that 4.8 million parents were not working because they were at home caring for a child not in child care or school.[3] In North Carolina, that means 119,263 parents.[4] It’s no wonder that nearly 40% of families with children in North Carolina reported having difficulty paying bills in the past week.[5]

North Carolina Economic Recovery and Growth. For economic recovery and growth, North Carolina needs a vibrant child care market—child care centers and family child care homes that are open for business and ready to enroll children up to program capacity. For too many programs, the reality is that parents remain on a waiting list because programs are struggling to recruit and retain staff. It’s a tight labor market, which has caused many employers to raise wages. Given that 71 counties in North Carolina paid child care staff at or below $12 per hour last year,[6] it’s not hard to understand why individuals who may be inclined to work in child care because they love working with children now have other options that pay more, often with less training and stress.

The Economics of the Child Care Business Model. More than 90% of NC Early Childhood Stabilization Grant applicants chose to address workforce compensation as a key investment of these funds.[7] In preliminary data reviewed, the great majority of applicants (79%) opted to increase base pay and/or benefits with another 13% using grant funds to provide staff bonuses.[8] Why? Because the labor market is tight, and in the absence of charging parents higher fees (which are already unaffordable for too many), there is no other current way for child care programs to be competitive against other community employers. Without staff, child care programs can’t operate (or can’t operate at capacity). When programs close or operate with fewer classrooms, parents have fewer choices. Parents with fewer child care choices may be less likely to rejoin the workforce, which undermines North Carolina’s road to economic growth instead of enhancing it.

Now is the Time to Rethink Child Care Funding. What concerns child care providers about the future is that the stabilization grants run out next year. The investments in staff wages aren’t sustainable over the long term. Across the five case studies in the CSSA issue brief[9] is the concern about what happens to program stability and staffing once the stabilization grants are spent. Recruitment and retention are already hard even with the supplemental stabilization money, but once that money expires, program directors fear a mass exodus of staff.

As I’ve said before, child care is a public good. Children, parents, employers and communities benefit when parents have access to child care. There are some short-term options and longer-term, but both require close review to determine how best to support the child care business model. On average, approximately 70% to 80% of a child care center’s expenses are related to personnel costs.[10] Therefore, addressing the wages paid to individuals working in child care is at the core of stabilizing programs and shoring up the industry (which ultimately has its investment return in more working parents and children who enter school ready to succeed).

The U.S. Treasury Department allocated Coronavirus State and Local Fiscal Recovery Funds to states, counties, cities and tribes to invest in recovery activities. Child care programs, facilities and wages specifically, are mentioned as eligible expenses. Funds must be obligated by December 31, 2024, and spent by December 31, 2026.[11] For North Carolina, at the state and local level, the investment of some of these funds in child care could help communities ensure that child care is available for parents. North Carolina received:

- $5.4 billion to the state

- $705.3 million for non-entitlement areas of the state

- $2 billion to counties, and

- $668.1 million for cities.

Another option would be for the state to invest general revenue funds to supplement current federal funds. These additional funds could help ensure that investments in child care are sustainable after the stabilization money is spent.

There are options to ensure that working parents have access to child care. These options involve stabilizing an industry that supports all other industries. What we know about the child care market even before the current public health pandemic was that the low wages paid to those working in child care acted to subsidize the cost for parents (i.e., without the low wages, affordability for parents would have been even more difficult). Child care is essential for the employment of parents. Economic growth depends on employment. A good start for discussion is North Carolina Governor Roy Cooper’s budget, which has $26 million invested in the Child Care WAGE$ program that raises average pay, reduces turnover and increases continuity of care. The budget expands access to early childhood education with investments in NC Pre-K and high-quality child care. Additional funds will be needed so let’s start now to plan for when the current child care stabilization money expires. Without a plan, child care is left to chance for parents.

[1] Committee for Economic Development of The Conference Board, The Economic Role of Paid Child Care in the U.S. – A Report Series, https://www.ced.org/paidchildcare. Labor Force Participation Across States by Female Marital Status and Children Ages 0-14 1977-2021.

[2] Committee for Economic Development of The Conference Board, The Economic Role of Paid Child Care in the U.S. – A Report Series, https://www.ced.org/paidchildcare. Labor Force Participation Across States by Female Marital Status and Children Ages 0-4 1977-2021.

[3] U.S. Census Bureau, Household Pulse Survey, Week 44 Household Pulse Survey: March 30 – April 11, 2022. Employment Tables. Table 3. Educational Attainment for Adults Not Working at Time of Survey, by Main Reason for Not Working and Source Used to Meet Spending Needs.

[4] Ibid.

[5] U.S. Census Bureau, Household Pulse Survey, Week 44 Household Pulse Survey: March 30 – April 11, 2022. Spending Tables. Table 1. Difficulty Paying Usual Household Expenses in the Last 7 Days, by Select Characteristics

[6] Fact Sheet on Early Childhood Teaching Staff Median Hourly Wages by Counties, NC Early Education Coalition, 2021. https://ncearlyeducationcoalition.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Workforce-Compensation-Fact-Sheet-3.31.21.pdf

[7] Child Care Services Association, Addressing the Early Childhood Workforce Crisis Through Stabilization Grants, April 2022. https://www.childcareservices.org/2022/04/27/addressing-the-early-childhood-workforce-crisis-through-stabilization-grants/

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, National Center on Early Childhood Quality Assurance, Guidance on Estimating and Reporting the Costs of Child Care, January 2018. https://childcareta.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/public/guidance_estimating_cost_care_0.pdf

[11] U.S. Department of the Treasury, Coronavirus State & Local Fiscal Recovery Funds: Overview of the Final Rule, 2022. https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/136/SLFRF-Final-Rule-Overview.pdf