The future of child care relies on the future of the child care workforce. Child care is a business, which I’ve written about many times before. However, given the current economy, it is important to think about the child care workforce, which like other workforces, is impacted by pay, overall compensation (such as benefits) and other factors (e.g., the pay and benefits paid by competing businesses in the community).

Many businesses throughout the country, including in North Carolina, are struggling to hire and retain workers in our current pandemic economy. Unemployment is down significantly since the spring of 2020, but in many states, it is still higher than it was in January 2020.[1]

In North Carolina, unemployment is down to 3.9%, lower than the national unemployment rate and close to the unemployment rate in January 2020 at 3.5%.[2] But, this masks several other important factors. In North Carolina, since January 2020,[3]

- the labor force participation rate is down 2.1% (i.e., in November, the labor force participation rate was 59.3% with about 66,300 fewer individuals in the labor force),

- the employment-population ratio is down 2.3% (i.e., in November, the employment-population ratio was 57%, with nearly 85,000 fewer people employed) and

- 264,543 individuals are either currently unemployed or have dropped out of the labor force.

The number of individuals quitting their job (about 4.2 million throughout the country), has led economists to call this period in time “the Great Resignation.” While the U.S. quit rate is 2.8%, in North Carolina, it is 3.4% (i.e., 157,000 individuals quit their job in October).[4]

The reason this pandemic economy is particularly challenging for the child care workforce is that for decades, child care was one of the lowest-paid jobs across occupations. Beyond low pay, workforce flexibility to work remotely (a benefit employers have significantly increased over the past 22 months) does not apply to the child care workforce. Child care is an on-site business.

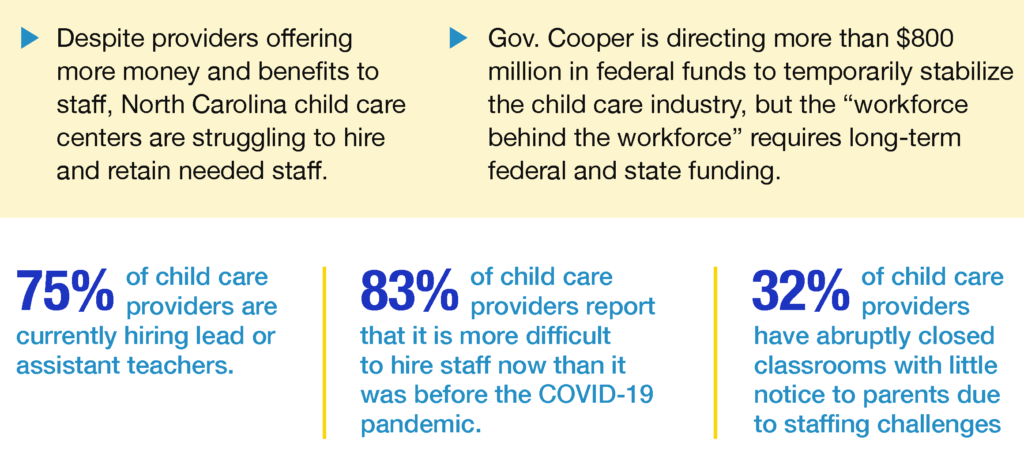

In North Carolina, a survey released in October commissioned by the NC Child Care Resource & Referral Council found that more than 80% of child care centers say it is more difficult to recruit and retain staff now than before the pandemic. As a result, the survey found that about one-third (32%) of centers have had to temporarily close classrooms due to the labor shortage.[5]

Child Care Services Association (CCSA) is proud to partner with the N.C. Division of Child Development and Early Education (DCDEE) on strategies to better support the child care workforce (e.g., Child Care WAGE$®, Infant and Toddler AWARD$® Plus, and T.E.A.C.H. Early Childhood® scholarships designed to increase compensation for child care workers based on credentials and higher education as well as child care stabilization grants to support programs). These are helpful strategies. But additional child care workforce strategies are needed.

The fundamental challenge for the business of child care is that operating budgets do not support wages high enough to recruit and retain staff (compared to other businesses within the community). NCDCDEE’s child care stabilization grants offer supplemental funding for programs that select one of two strategies to increase workforce compensation:

Option 1. Provide Staff Bonuses

- Programs will provide bonuses to their staff

- Must submit a bonus plan to describe bonus schedule to teaching and non-teaching staff

Option 2. Increase Staff Base Pay and/or Provide or Increase Benefits

- Programs will increase base pay by implementing a salary scale for teaching and non-teaching staff and/or provide or increase benefits

Programs that select Option 2 receive higher grant awards than Option 1. Stabilization payments to programs will be made through June 2023.

While this is an enormous opportunity to boost wages for the child care workforce, it is temporary. A permanent solution to the child care workforce wage and benefit challenge is needed.

The child care workforce challenge transcends states. The first step to addressing the child care wage problem is to develop a wage scale. CCSA’s National Center’s Moving the Needle workgroup worked with stakeholders to design a voluntary wage scale. North Carolina centers receiving stabilization grants are encouraged to use the wage scale to help inform program workforce pay. Many states are using stabilization funding provided through the American Rescue Plan to both stabilize the child care market and boost child care wages (either through bonus and/or retention grants or through grants to programs to design their own workforce strategies).[6]

This period of temporary child care funding increases offers states an opportunity to provide a bridge for longer-term solutions. Some states have developed compensation wage scales. Currently, 23 states and the District of Columbia are participating in the T.E.A.C.H. scholarship program[7] and five states participate in the WAGE$ program.[8] Other states are pursuing innovative approaches through tax credits or apprenticeships.[9] Some states have a combination of approaches including cost modeling, which builds in higher wages and pay parity based on credentials and experience.[10]

Child care is not only a business, but it is also a public good—one that is critical to economic recovery so parents can work. The pre-pandemic child care model was expensive for parents yet failed to pay the child care workforce livable wages. In this pandemic economy, with supplemental federal funds, temporary solutions can and are being developed to better address the child care worker compensation challenge.[11]

What is needed is a way forward – a post-pandemic strategy to better compensate the child care workforce. This could be through federal legislation such as a potentially revised Build Back Better or could be through a series of well-designed supports to supplement what the market by itself cannot address. These policies aren’t mutually exclusive, but it is imperative that we begin the conversations now for the post-pandemic stability of the child care market.

It is time to build the bridge between supplemental federal funds for child care that have been provided over the past 22 months and the post-pandemic child care landscape upon which parents and employers will depend. Economic recovery and growth depend on it.

[1] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Civilian Unemployment Rate.

[2] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Local Area Unemployment Statistics.

[3] Ibid.

[4] U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Table 4. Quits levels and rates for total nonfarm by state, seasonally adjusted.

[5] NC CCR&R Council, North Carolina Staffing Survey, October 2021.

[6] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Child Care Technical Assistance Network.

[7] T.E.A.C.H. Early Childhood® National Center.

[8] T.E.A.C.H. Early Childhood® National Center, Child Care WAGE$®.

[9] Harriet Dichter and Ashley LiBetti, Improving Child Care Compensation Backgrounder, October 2021 (the BUILD Initiative, 2021).

[10] Ibid.